Desk Report:

The news came to the newspapers almost silently—it didn’t even catch the eye. Maybe because it wasn’t a particularly provocative issue; or because it wasn’t a major crisis. But ultimately, the news carries a sinister message. In Bangladesh, nearly 900,000 young people with the highest university degrees are unemployed. In 2013, the number of unemployed young people with university degrees in Bangladesh was 200,000. So, the number has increased more than fourfold in the last 12 years. If the number of unemployed people in the country is 2.7 million, then one-third of them have university degrees. This picture naturally raises several questions. For example, if the country’s highest education cannot ensure employment for the youth, then is university education in this country a waste, has it lost its relevance? Isn’t this huge number of unemployed youth a waste of resources and opportunities? Or how will Bangladesh compete in the 21st century world with such a strategy?

To answer these questions, let’s look at the overall picture of youth unemployment in a slightly different way. One. Data shows that among unemployed youth with university degrees, there are 600,000 men and 300,000 women. There may be two reasons for this. Even with university degrees, fewer women enter the labor market. As a result, the fact that they are less likely to be unemployed may be a reflection of that reality. Or, it may be that only a small number of young women with university degrees are unemployed. Two. Among unemployed youth with various levels of education, the rate of youth with university degrees is the highest. While the unemployment rate among youth with secondary education is 3 percent, the rate among youth with university degrees is 14 percent—more than four times higher. Three. In Bangladesh, about 8.6 million young people are not in education, work or training—2.8 million of them are men and 5.8 million are women.

Keeping this context in mind, let us analyze the questions raised. First, if we put aside the sophisticated and subtle objectives of university education for the time being, one of the most important goals of obtaining a university degree is to get a good job. Then it appears that for 900,000 young people, that goal is not being achieved. At the same time, it appears that those who have no formal education, those who have primary or secondary education, are getting jobs; but the highly educated are not finding jobs. Many have called this a conundrum, while others have also raised questions about the relevance of higher education in the workplace.

To answer this question, it is necessary to first say that in the labor market where workers with primary or secondary education work, the demand for skills is general, with which they can complete simple tasks. There is no need for high-quality specialized skills in that market. Therefore, people without formal education, with primary or secondary education, also find work in that market. There is a connection between the demand for skills in the labor market and the supply of skills in the labor market.

But in the labor market where university-certified human resources are employed, there is a considerable gap between the knowledge and skills that are expected for employment and the knowledge and skills that university-certified young people come out with. The heads of our industrial institutions often complain that the country’s higher education sector cannot provide the kind of professional knowledge and skills that they need. As a result, the employment of our highly educated youth is hampered.

The subject in which the university degree is obtained is also important. For example, 23 percent of graduates with a degree in political science are unemployed, while the unemployment rate among graduates in English is 0.17 percent. It is important to remember that the world of work, work subjects and work patterns are changing rapidly in the current world. One reason for this is of course the revolution in information technology, but another reason is the structural changes in the production and service sectors. As a result, the demand for new professional knowledge and skills is being created. Our higher education system and the educational structure of our universities are not able to create that knowledge and skills. As a result, the number of unemployed people with university degrees is increasing and at the same time, questions are being raised about the relevance of current higher education in terms of employment.

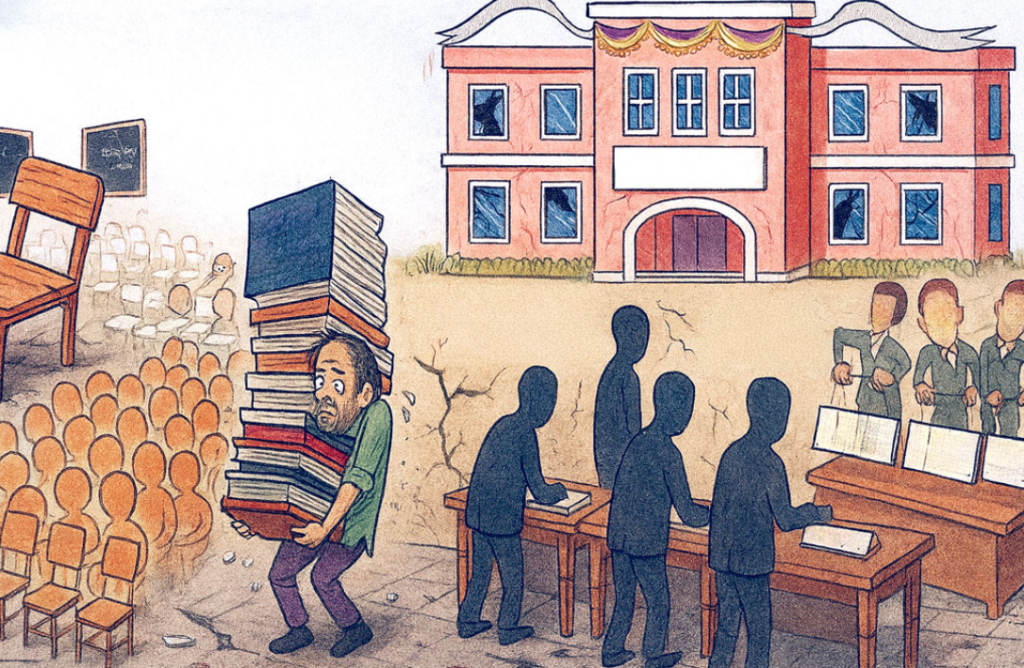

There are other dimensions to the disconnect between higher education and employment. The economy of Bangladesh can currently absorb 300,000 graduates into employment. However, Bangladesh’s higher education system produced about 700,000 graduates in 2022 alone. Where the supply is more than double the demand, high unemployment is bound to occur. Another reason for this huge supply is the unprecedented expansion of the establishment of universities in Bangladesh.

There are currently 56 public universities in Bangladesh, up from 53 three years ago. With the establishment of 15 more private universities in the last three years, the number of private universities in our country is now 116. Needless to say, a large portion of these universities in the country award certificates; but do not create the sought-after skills. For example, Bangladesh National University produced 61 percent of the country’s 700,000 graduates in 2022. On the other hand, 16 percent of unemployed graduates are graduates of that national university.

There is also a macro perspective of high unemployment among university graduates. At the heart of that perspective is jobless growth. The Bangladesh economy has grown in recent years; But it did not create jobs. The government’s entire focus was on growth, job creation.

Not in the direction. Currently, investment in the private sector has decreased, employment opportunities have decreased. There is a disconnect between national income and employment in Bangladesh’s sectors as well. The country’s agricultural sector contributes only 11 percent of the national income; but employs 45 percent of the people, but there is pseudo-unemployment and underemployment. The industrial sector contributes 37 percent of the national income; but its share in employment is only 17 percent. Although the service sector contributes 51 percent of the national income, its share in employment is 38 percent.

There is another reason for the high unemployment among university graduates. People without formal education, primary or secondary education, do not scrutinize their employment that much. They take whatever is available. But university graduates consider various factors in their employment decisions, including the social status associated with the job. They do not consider all types of available work. And their vetting is also quite difficult. As a result, their employment decisions are not very flexible.

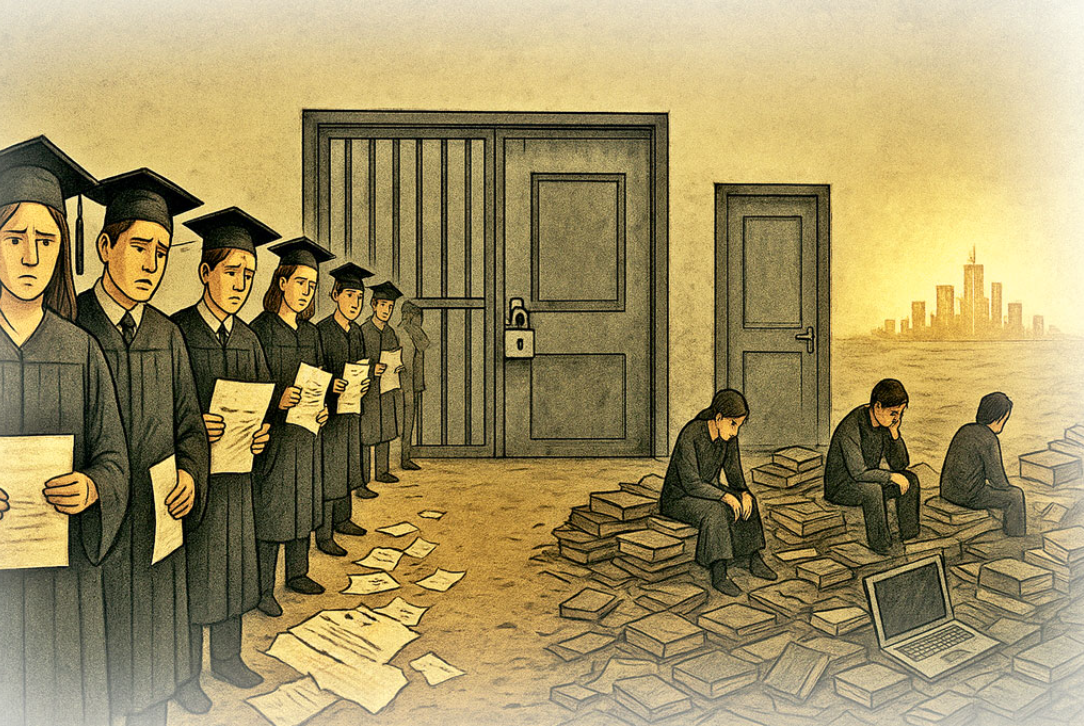

Two dimensions of this broad picture are extremely important. Being unemployed even after obtaining a university degree creates a sense of despair among the youth. If the period of that unemployment is prolonged, it deepens the above despair. At the individual level, that despair has a financial and psychological dimension; but at the collective level, that despair has a social and political dimension. Youth despair is not only negative; it is not desirable at all.

At the same time, in a country where 900,000 highly educated youth are unemployed and where 8.6 million youth are out of education, employment and training, it is a huge waste of resources. Yet youth is a great asset in economic dynamism and social change. If the vitality, risk-taking ability, creativity and inventiveness, courage and morale of the youth are not properly utilized, it is an unimaginable waste of a rare resource.

The world is changing rapidly. In that context, our youth will have to compete in a dynamic world. For that, we have to prepare quickly by preventing the waste of youth energy, increasing their capabilities, and utilizing them. Because, we do not have much time in our hands.

Author: Economist